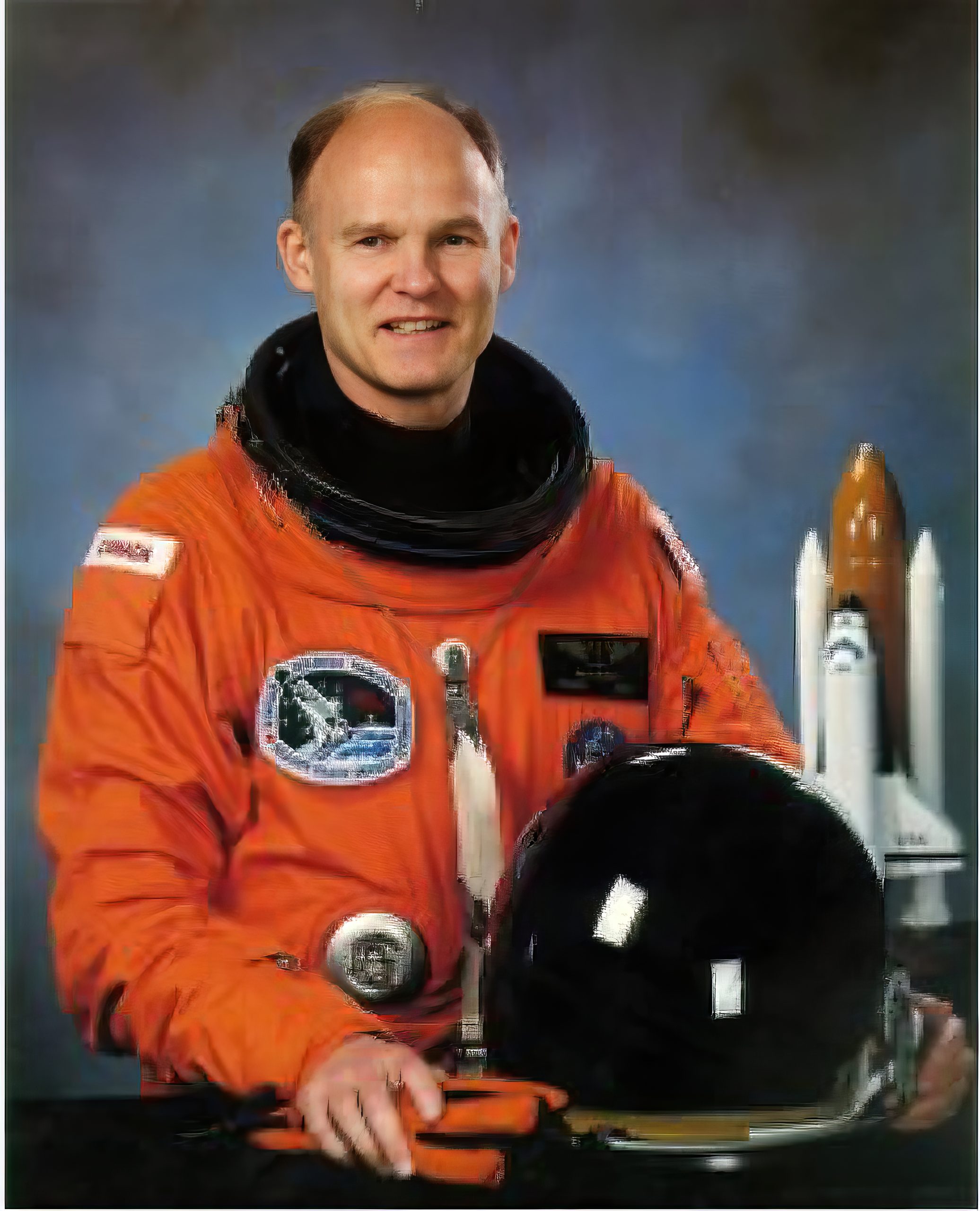

Kenneth Money

Birth Date: January 4, 1935

Birth Place: Toronto, Ontario

Year Inducted: 2024

Awards: Academician of the International Academy of Astronautics, Fellow in the US Aerospace Medical Association, Wilbur R. Franks Award, Meritorious Service Cross, Kent Gillingham Award

Kenneth Eric Money was an accomplished and highly respected doctor and research scientist whose expertise on the inner ear and its relation to balance, disorientation, motion sickness, and the biological effects of space made him an integral figure in the history of Canadian aviation and aerospace.

Success in Academics and Sport

Born in Toronto, Ontario in January 1935, Ken attended North Toronto Collegiate high school in Toronto and then Noranda High School, in Noranda, Quebec. He excelled at both academics and sports, especially track and field. From high school he headed to the University of Toronto, where he took a BSc in physiology and chemistry in 1958. He then went on to earn his MSc and PhD in physiology, also at U of T.

While at university, Ken played for the Varsity Blues, competing in swimming and track and field. He was an expert high jumper for the team, eventually jumping a personal best of 2.07 meters – a Canadian record at the time. Between 1955 and 1959 he was Canadian high jump champion five years running, and in 1956 Ken represented Canada at the Summer Olympics in Melbourne, Australia. He placed fifth, jumping 2.03 meters. Two years later he was a member of the Canadian Empire Games team. He remained a lover of sport throughout his life, competing in the World Master’s Games several times; in 1985 he placed second in Badminton and first in high jump, and in 1989 he won the American Master’s Badminton championship held in Miami. The Canadian Sports Hall of Fame, the Canadian Forces Sports Hall of Fame, and the University of Toronto’s Hall of Fame have all recognized Ken’s achievements in sport.

Joining the RCAF

In 1954, while at the University of Toronto, Ken joined the Royal Canadian Air Force. He trained at Moose Jaw before going on to serve with 400 Squadron, then a reserve search and rescue unit. He was twice involved in successful missions to the Canadian north. In 1958, he had the opportunity to fly the Mk V F86 Sabre and proudly joined the Mach Busters club, flying faster than the speed of sound. Ken graduated from the National Defence College in 1972 and eventually reached the rank of Major. Having flown about 4,000 hours, he retired from service in 1981, but not before learning to pilot the CH-136 Kiowa helicopter, an achievement he remained very proud of.

Research in Vestibular Physiology

Professionally, Ken joined the Defence Research Establishment Toronto, later the Defence and Civil Institute of Environmental Medicine (DCIEM), as a research scientist in 1961. He soon developed a research program, which built on his doctoral work, examining vestibular (inner ear) physiology with a focus on aviation and problems of motion sickness, spatial disorientation, and vertigo. His work on the effects of microgravity on the inner ear piqued the interest of NASA, which was concerned about astronauts suffering from motion sickness. Having been invited to advise the US Space agency in 1962, by 1965 he was taking part in its first symposium on The Role of the Vestibular Organs in the Exploration of Space, where he contributed a paper, “Some Vestibular Responses Pertaining to Space Travel”. NASA had chosen well; he continued to participate in subsequent symposiums, delivering papers examining how gravity and viscosity affect endolymph and perilymph, tests on semicircular canals and otoliths in cats, the neural mechanisms underlying the symptomology of motion sickness, and the vestibular system of the owl. In Ken’s case, theory and research were both used to inform practice, and he continued working with NASA to help test its astronauts through screening and training for vestibular integrity – a position that led him to lobby to have Canada included in the American space program.

Back at DCIEM, Ken’s research continued to break new ground, often in ways that eventually enhanced the safety of the entire space community. He authored many influential articles, including his 1970 piece in the journal Physiological Reviews, “Motion Sickness”, which remains regularly cited. He undertook experiments on semicircular canal plugging and then invented and demonstrated a resulting surgical operation to treat types of dizziness. At his Toronto lab, he designed important research and testing tools, including a unique three-axis simulator (the Precision Angular Mover, or PAM), which spins humans on all three axes, to study how the balance organ can produce signals resulting from disorientation and motion sickness. And he made important contributions to the development of the peripheral vision horizon display, or Malcolm Horizon, to lessen spatial disorientation.

Becoming An Astronaut

When Canada announced its own astronaut program, Ken was among the thousands to respond. Given his pre-existing work with NASA, mixed with a unique combination of skills: research scientist, military pilot, and Olympian, he was perhaps the best qualified Canadian to apply. Members of the selection committee agreed, believing that Ken ‘stood out’. As living proof of his qualifications, when the acceptance call came that he had been chosen as one of Canada’s first six astronauts, Ken was in Houston supporting a NASA mission at the Johnson Space Centre; and, as part of their preparations, it was to his lab that the new Canadian astronauts headed for motion sickness training and tests using the PAM and coriolis chair. Astronauts like Steve MacLean noted that the work Ken did with him meant that “I had no issues with vertigo on my space walk” because of having learned to “recognize, minimize and even avoid the onset of vertigo.”

After Marc Garneau (CAHF, 2008) was selected to fly as Canada’s first astronaut, Ken worked to prepare the Canadian life science experiments for the flight, a portion of which – SASSE (Space Adaptation Syndrome Supplementary Experiments) – he co-designed with Douglas Watt of McGill University that were part of his ongoing study of motion sickness, disorientation, and sense of body position in microgravity. Ken also continued to collaborate with his colleagues on vestibular experiments carried out on other space flights, including STS-9 – the first Spacelab mission (SL-1), the 1985 Spacelab D-1 mission, run by the European Space Agency, and NASA’s Space Life Science-1 (SLS-1) launched in 1991 in a module housed within the shuttle Columbia’s cargo bay in 1991, as well as 1993’s follow-up mission, SLS-2.

A Return to DCEIM Research

With the success of Garneau’s first flight, Roberta Bondar was selected to fly STS-42, with Ken as backup. The mission’s main goal was the study of living organisms in a pressurized Spacelab module, the International Microgravity Laboratory-1. Although disappointed at being assigned a backup role, Ken ably supported the mission and served as the Spacelab Payload Operations Controller, which included conducting daily press briefings. While he would have preferred to have been aboard the shuttle, he was ideally suited for the task of explaining the complicated experiments carried on Space Shuttle Discovery to a general Canadian audience.

Having accepted that he was unlikely to secure a space flight as a Canadian astronaut, Ken resigned from the Canadian Space Agency upon completion of STS-42 and returned to DCEIM, now as senior scientist and the first Chair of the Human Research Review Board. But this did not end his involvement with aerospace. He chaired the Human Factors Committee of the International Academy of Astronautics and was editor and co-author of its 1996 Mars Cosmic Study. From 1999 through to 2003 he sat on the Board of the Canadian International Air Show. He served also as president of the National Space Society, the American educational and scientific organization that advocates for the study and exploration of space and, later, he sat on its Board of Governors and was a director from 2004 to 2016.

Awards and Recognition

Ken’s expertise as a specialist in understanding the science of disorientation, motion sickness, and vertigo was well recognized. In 1981 he was selected as the W. Rupert Turnbull lecturer at CASI. Three years later he was elected Academician of the International Academy of Astronautics, and in 1985 he was elected as Fellow in the U.S. Aerospace Medical Association. The following year the Canadian Society of Aviation Medicine presented Ken with the Wilbur R. Franks Award. He delivered the Grass Foundation Neurosciences Lectureship at Penn State University in 1989 and, in 1992 he was asked to present the Wellmark Lecture for the Canadian Association for Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases. In 1994, the Governor General awarded him the Meritorious Service Cross. He received the Kent Gillingham Award from the Aerospace Medical Association in 2000. Despite these and other accomplishments, what Ken took most pride and pleasure in was being a father and grandfather, a role for which he rose continually to new heights.

To return to the Inductee Page, please click here.