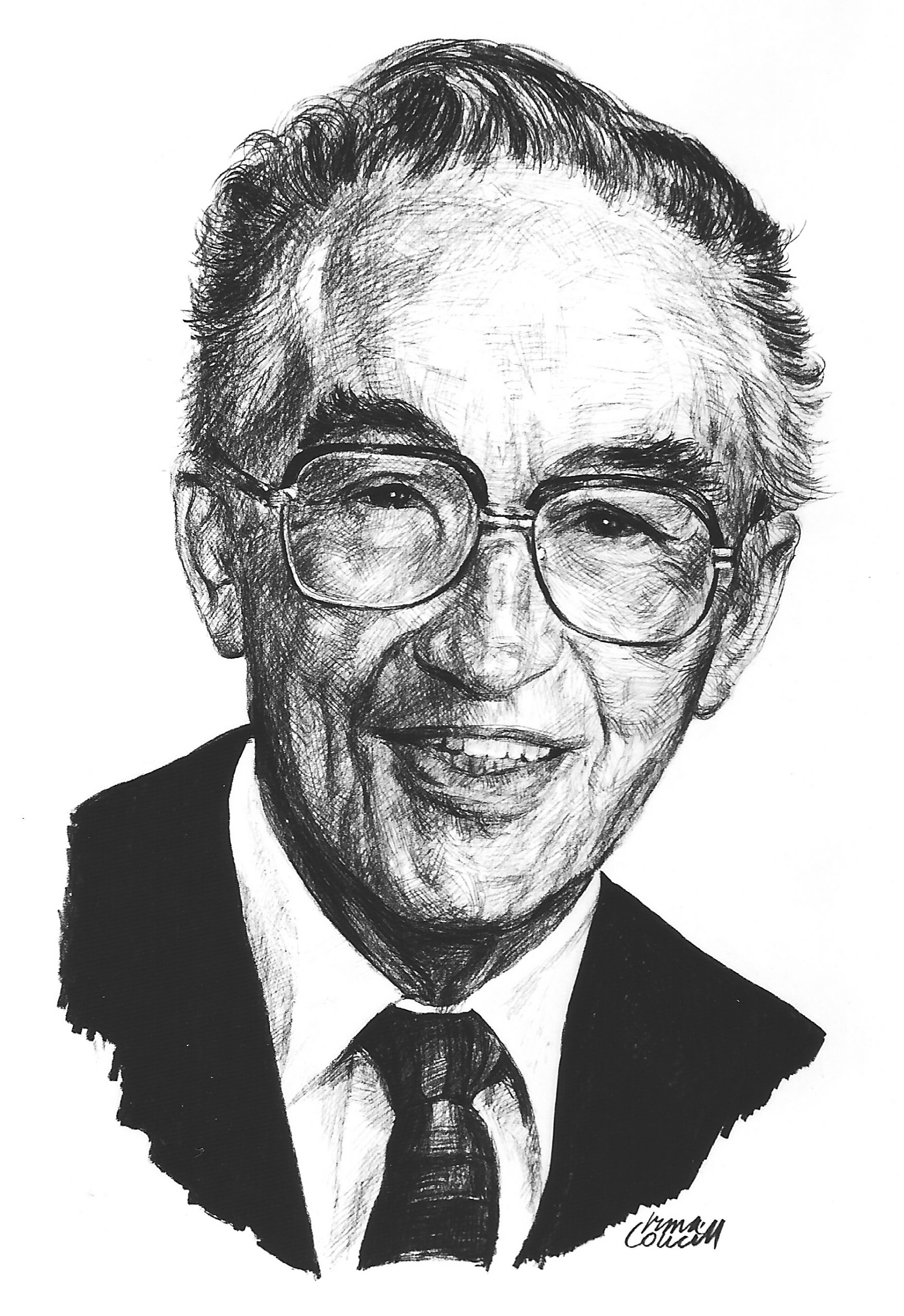

Harold Rex Terpening

Birth Date: July 23, 1913

Birthplace: Wainwright, Alberta

Death Date: July 15, 2018

Year Inducted: 1997

With innovative ability, resolution, and courage, in the most arduous situations, he kept the early aircraft flying. His skills as an air engineer, and later as a manager, span the history of aviation from the earliest bush operations to the modern jet era, and are of significant benefit to transport aviation in Canada

Flying in Fort McMurray

Harold (Rex) Terpening was born on July 23, 1913, in Wainwright, Alberta, and moved to the Fort McMurray area of northern Alberta at an early age. The educational facilities at that frontier village were meagre but fortunately a school program was soon offered.

Fort McMurray became the base for several early aviation companies and there were many opportunities to learn the skills required of a maintenance engineer. By working without pay, Terpening obtained ample experience on every type of maintenance and repair procedure that could be carried out in the field. Only part-time jobs existed and these he augmented by trapping, cordwood cutting, and working on the river boats. Thus, he survived until he could qualify for his Air Engineer's Licence and obtain permanent employment with Canadian Airways Limited in 1935.

An Air Engineer

For the next several years Terpening flew as air engineer with many well-known pilots throughout the Canadian Arctic. These were the beginning years for aviation in the north, with the equipment untried, the facilities primitive, and the terrain unmapped and largely uninhabited - a time of hardship and hazard for all.

Breaking Through the Ice

In November of 1934, Terpening and Canadian Airways pilot Rudy Huess broke through the ice with a fully loaded aircraft. Extricating the passenger who was trapped between the load and the roof, Terpening forced open the cabin door and they made their escape.

Cold Weather Repairs

In 1936, on a trip with Matt Berry, their aircraft was severely damaged during a desperate landing in fog and darkness at Fort Good Hope. Poor visibility caused them to collide with a pile of gas drums, breaking one ski, twisting the ski pedestal, bending the propeller, and tearing out fuselage cross-members. Temporary repairs in order to ferry the plane to Fort McMurray required a week. Temperatures were below -60°F (-51°C).

Bad Weather Flying

Also in 1936, Terpening and Berry flew a Junkers to isolated Paulatuk, 400 miles east of Aklavik, to bring out Bishop Falaize and his party, marooned when their schooner was caught in early ice between Coppermine and Letty Harbour. To make matters worse for the small group, most of their food supply was lost to pillaging polar bears. After their arrival at Paulatuk, Terpening and Berry were storm-bound for ten days and were becoming increasingly short of fuel, food - and daylight! An attempt to leave Paulatuk on December 14 failed due to white-out conditions. Airborne once again on December 19, they survived a violent landing during another white-out, and the group of six adults and four children spent a bitterly cold night on the Barrens, huddled together in a makeshift shelter under the aircraft. They arrived at Aklavik the following day, December 20, with their fuel exhausted. Years later, Berry called this Paulatuk trip the most hazardous and difficult he had ever experienced.

Rescue Mission

In November of 1937, Terpening and Huess flew from Edmonton to Aklavik with a load of radio equipment urgently needed in the search for Russian trans-polar pilot Levanevsky and his crew. With the southern rivers still not frozen over, they loaded gasoline into the aircraft cabin, transferring this to the wing tanks in flight. With this added range they were able to reach a safe landing area, after 500 miles of poor visibility and icing conditions.

Cold Aircraft Repairs

In 1938 Terpening, assisted by engineer Ted Bowles, was assigned to salvage a Noorduyn Norseman, CF-BAU, damaged near Yellowknife. They lived for five weeks in a tent which was set up to cover the front end of the aircraft, providing shelter while they carried out repairs in temperatures down to -50°F (-46°C).

Oil Dilution System

Following a propeller inflicted injury in 1938, Terpening was transferred by Canadian Airways to Brandon, Manitoba, where he worked with Albert Hutt on developing the first Oil Dilution System. This involved injecting gasoline into the engine oil at shutdown, preventing it from congealing in the cold and making draining unnecessary. It allowed the engine to be re-started without the laborious and risky process of preheating both oil and engine. The system was installed in Junkers CF-AQW, which was then moved to Stevenson Field at Winnipeg, Manitoba, where Terpening carried out the cold weather starting procedures with Tommy Siers. Numerous equipment modifications followed, but success was finally achieved on February 21, 1939, with the first successful start of a diluted, cold-soaked engine. The system allowed the engine to start at temperatures down to -44°F (-42°C).

Rescue in the Arctic Circle

In early winter of 1939, Terpening was engineer on a rescue mission to Repulse Bay, located inside the Arctic Circle, 700 miles (1,126 km) north of Churchill, Manitoba. A young priest was suffering with severely frost-bitten hands after falling through thin ice on a hunting trip, and by the time a request for help was received, gangrene was beginning to destroy his right hand. Pilots W.A. Catton and A.J. Hollingsworth left Winnipeg on November 27 in a wheel-equipped Junkers, flying through low and ice-laden clouds to God's Lake, where they changed to skis. They pushed on to Churchill, Eskimo Point, Chesterfield, and finally, to Repulse Bay. Poor visibility and endless blizzards caused agonizing delays. They finally returned to Winnipeg on December 20, after completing the longest emergency flight in the history of the company.

Training Others

With the start-up of the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan (BCATP) in 1940, Terpening was transferred to No. 2 AOS (Air Observers School) at Edmonton and was tasked with sorting out numerous initial problems of untrained personnel, unfamiliar aircraft, and lack of spare parts. In 1941 he became Maintenance Superintendent of the newly opened No. 7 AOS at Portage la Prairie, Manitoba, and soon developed his department to an award-winning level of efficiency. After one year, Terpening was recalled to airline activities with Canadian Airways at Edmonton. At this time, several small companies, including Canadian Airways, were brought together to form Canadian Pacific Air Lines (CPA), with maintenance under the direction of Albert Hutt.

Aerial Survey Work

During the early 1940's, Terpening was assigned to do aerial survey work for the Canol Pipeline Project being developed to bring crude oil from Norman Wells to Whitehorse. The United States Air Force used a twin-engined Douglas C-47 for this work, which proved to be an arduous task, as Terpening's camera position was unheated, there was little shelter from the slipstream and air temperatures were in the -20°F (-6°C) range.

CP Air

From 1946 to 1950, he was stationed at Regina, Saskatchewan, as District Chief Mechanic, maintaining CPA's Lockheed Lodestar and Douglas DC-3 aircraft. He was later moved to a similar position in Vancouver, British Columbia, in charge of maintenance in the B.C. and Yukon districts, working on aircraft such as the Convair 240 and DC-4, the DC-6B and the Boeing 737.

This was a time of dramatic change for CPA, including a change in name; in 1968 CPA became known as CP Air. The airline dealt with rapid expansion, developing new routes, setting up new field stations, and hiring and training new personnel. There were added responsibilities for Terpening, and he became Manager, Line Maintenance, for the airline.

At the time of his retirement in 1978 he was responsible for maintenance activities for CP Air in western Canada, and for all its international bases in Europe, Central and South America, the Pacific and the Orient. Rex & his wife Trudi lived in Surrey, B.C.

Following retirement, Terpening has endeavoured to preserve, with text and photographs, some record of the early aviation history of the north during the buy flying days of the 1930's. Several of these stories have been published in Canada's leading aviation historical magazines. His book, "Bent Props and Blow Pots" (2003) is considered by many to be the best book written on bush flying.

Harold (Rex) Terpening was inducted as a Member of Canada's Aviation Hall of Fame in 1997 at a ceremony held at Calgary, Alberta. Rex and Trudie spent many years retired in the lower mainland of B.C. and Rex passed away on July 15, 2018 - just 8 days short of his 105th birthday.

To return to the Inductee Page, please click here.